“It may not be good for America, but it’s damn good for CBS.” – Les Moonves, CBS Chairman

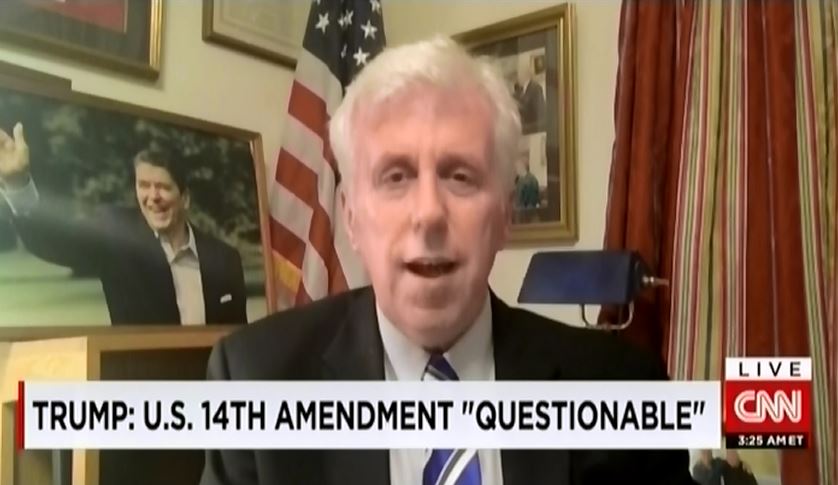

The Trump campaign and subsequent administration reinvigorated the media industry. Throughout the divisive 2016 election cycle and during the first year of the Trump presidency, the sheer amount of newsworthy content has dwarfed the content generated during previous administrations. Trump’s unabashed willingness to break political norms and his confrontational rhetoric grabbed the attention of the media and never let go.

I would argue that Trump is the most recognizable name in the world right now, thanks to the media’s appetite for Trump coverage. The media essentially gifted Trump’s campaign millions of dollars of airtime by covering his campaign rallies in their entirety on cable news, and he perverted the term “fake news” to mean any media source that criticizes him (instead of the original use to mean literal fake news created by Russians in an attempt to subvert American democracy). The primacy of Trump news has spurred an even larger drive to tribal partisanship, but it also has amplified political participation and has made it more difficult to be apathetic toward politics.

But more news means higher profits for media sources, just as Mr. Moonves from CBS remarked. These news networks self-define as guardians of truth, but in reality their business model profits off of crises, controversy, and inflamed tension, which lead to more viewers and clicks. Counterintuitively, being labeled as “fake news” by Trump or his followers allows the media organization to grovel for donations through a veiled appeal to their consumers’ fears about the possible death of truth. This is not to say that the work of traditionally leftist media organizations is inherently disingenuous at the moment—I believe the New York Times, Washington Post, ProPublica, and some parts of the cable networks are doing a vital job in investigative journalism and in analyzing what news actually matters, but the profit incentive undoubtedly exists to work in a time like this where such journalism is necessary. The 24 news cycle is less profitable during a time of peace, predictability, and stability. But how did we get here? Why is our media system so obsessed with Trump content?

There is a political science theory by Steven Livingston of George Washington University named the CNN Effect that I believe can help explain how we have gotten to where we are today. In general, the theory posits that 24 hour news networks like CNN, Fox News, and MSNBC tend to pick up and report on stories once they reach a crisis point. These networks rarely report on the events leading up to the crisis or the aftermath of the crisis, thus only showing viewers the crisis itself. Most commonly, this theory is applied to foreign policy and natural disasters; for example, the major media networks did not cover the situation regarding the Rohingya in Myanmar until the genocide and crisis began last fall. Or, consider the recent impact Hurricanes Harvey and Maria had on Houston and Puerto Rico. These areas were in the news for a few weeks as the hurricanes hit, but they have fallen out of the news, even as countless Puerto Ricans continue to go without power. These news networks jump from crisis to crisis to generate clicks and views and to maximize the political relevance of their content. The CNN Effect often impacts policy-makers by highlighting humanitarian issues around the world, which can drum up support for interventions to help the affected people.

But I believe the CNN Effect played a role in the Trump-centric media landscape we have today. Before Trump arrived the 24 hour news cycle struggled to fill every hour with meaningful news stories—like I said before, stability and predictability are unprofitable. But with Trump’s campaign came salacious tweets, offensive comments, and personal attacks, which could be transformed into hours-long, crisis-like debates between pundits on both sides, each volleying their talking points back and forth until the next story rolled in. Cable news got their wish—enough content to fill 24 hours each day, but at what cost? In this media environment, the announcement of a DoD program that investigated UFOs hardly registered a response from the public. And the actual, sitting President of the United States tweeted about the size of his nuclear button among many other egregious topics that would be damning to any other politician. Last week’s Trump news is replaced by this week’s news, and these networks rarely come back to the previous stories to discuss the aftermath. The rise of Trump must be attributed to at least some extent to the media’s opportunism and profit-seeking behavior in the run-up to the 2016 election, and thus any real crises that emerge from the Trump presidency must also be owned to some extent by the media.

So how could we change our media system to combat profiteering incentives for unstable politics and perpetual crises? One option could be to change the U.S. media landscape to closer mimic the UK’s, where a state-owned media corporation, the BBC, acts as the main news source for most citizens. While other media organizations exist and reach citizens, e.g. Sky, ITV, The Guardian, The Telegraph, and others, the BBC is and always will be the main source of news in the UK. The U.S. does have PBS, but it is nowhere near as funded or popular as the BBC is in the UK. I hesitate to imagine what may happen to a state-sponsored news organization in the U.S., however. The BBC has created its own norms and institutions that protect it from being partisan, and yet it still gets accused of liberal bias. If PBS was the BBC of the U.S. it could be shaped by the party in charge at will, which may only make things worse.

Another option to reform our media system could be to get the Associate Press to agree to stricter requirements for objectivity and clearer labeling of opinion journalism, which too often masquerades as news on Fox News and MSNBC in particular. We also need to celebrate journalism that focuses on good news, like how crime rates continue to fall each year. The CNN Effect leads to hyper-coverage of every mass shooting and every gruesome crime committed, which deceives citizens into believing that crime rates are getting worse. Media sources must be incentivized to deliver contextualized news that represents reality.

A last option to change our media for the better would be to focus on media analysis during school. When I was in fifth grade, I remembering have a class in a computer lab where I was told to read an article and then talk about whether or not I believed it was truthful. My article was about pop tart blowtorches; my friend’s article covered jackalopes. I believed these things existed until my teacher told us these were all fake—that lesson has stuck with me, as it was the clearest example of the necessity of skepticism in media consumption. Similarly, a teacher in California showed his students how to identify fake news, and now they question every assumption and book they read. We need to incorporate critical analysis of the news and of media more generally into our curriculum. In our tribal media environments where we get our news from sources who think like we do, the importance of skepticism cannot be understated. By practicing skepticism, our bubbles would be a little less rigidly defined.

America’s media system begged for an administration like Trump’s. Their 24 hour news cycles were not satiated in the past, and suddenly they have an endless supply of content and crises to dissect and debate, putting the CNN Effect in full swing. The testier the time, the better their profits are, but the incentives do not have to be aligned this way. By encouraging stricter accountability to objectivity and contextualized news, along with better education that warns against trusting everything you read, we can redefine a healthier media system.